APRIL 2024 MEMBER NEWS

-

VIRGINIA

The Virginia Workers’ Compensation Commission is pleased to announce the reappointment of the Honorable Wesley G. Marshall as Commissioner for his third consecutive term. Commissioner Marshall’s extensive experience and unwavering dedication have been invaluable assets to the Commission since he began his tenure in 2012. Before his work as a Commissioner, he represented plaintiffs in workers’ compensation, employment, and other civil litigation matters as an attorney in private practice for 25 years. In recognition of his outstanding contributions to the field, Commissioner Marshall was inducted as a Fellow in the College of Workers’ Compensation Lawyers in 2015. He was appointed as President of the Southern Association of Workers Compensation Administrators in 2021, highlighting his leadership in the field of workers’ compensation. Commissioner Marshall currently sits on the Boards of Directors for the International Association of Accident Boards and Commissions (IAIABC), the National Association of Workers’ Compensation Judiciary, and Kids Chance of Virginia.

Since 2012, Commissioner Marshall’s dedication and commitment to serving injured workers, victims of crimes, employers, and related industries have been instrumental to the Commission’s mission. The Commission invites everyone to join in congratulating him on his reappointment and continued service to the Commonwealth of Virginia.

OCTOBER 2023 PRESIDENT’S LETTER

Greetings from the President

By Sheral C. Kellar

Workers’ Compensation Judge – Chief

Office of Workers’ Compensation Administration

Louisiana Workforce Commission

I learned a jingle in elementary school. For some unknown reason, it is on auto-repeat in my head.

“We’re all in our places, with smiling new faces. Oh, this is the way to start a new day!”

In early August, my tenure as President of SAWCA ended. I wanted to sing the jingle, as I opened SAWCA’s annual convention in Amelia Island, but I did not. As I begin my tenure as President of the NAWCJ, I wanted to open my NAWCJ college host day with “We’re all in our places …”, but again I did not. Tourgee Debose, my piano teacher of 10 years, said practice makes perfect. My daughter says practice doesn’t make perfect, practice makes permanent. I am inclined to believe my daughter. The song never ends. It is permanently in my head!

As SAWCA president and now as NAWCJ president, I looked out at the smiling faces of hundreds of SAWCA and NAWCJ attendees anxiously awaiting the sage presentations of industry leaders, attorneys, judges, and others. They were not disappointed. To stimulate dialogue and debate some presenters exercised the Socratic Method. Others presented materials that contained no answers, only more questions. These presentations provoked critical thinking in areas yet to be confronted. Smiling faces in deep thought! Now, this is the way to start a new day.

On Wednesday, August 23, 2023, the gavel passed from immediate past-President, Honorable Pam Johnson of Tennessee, to me, Sheral Kellar, of Louisiana. I have lofty goals for the association. As President, I hope to provide leadership that will:

- Grow the association;

- Increase the number of participants at the annual college;

- Continue the collaboration with other stakeholders to present educational forums regarding workers’ compensation;

- Support the Lex and Verum by providing frequent news of interest to our members; and

- Encourage the teaching of workers’ compensation in law schools

I may not achieve all of them, but I believe it is better to shoot for the moon. Even if I miss, I’ll land among the stars. (thank you Leslie Brown). I’m excited. I am honored and extremely humbled by your confidence in my ability to lead the association. With your help and your guidance, we can achieve these goals and so much more. This is my start of a brand new day. I’m smiling at the many possibilities. Let’s end like we began, “We’re all in our places, with smiling new faces. Oh, this is the way to start a new day!”

ARE YOU READY?

PEOs – HOW TO PROSECUTE AND DEFEND CASES INVOLVING EMPLOYEE LEASING AGREEMENTS

By: Hon. Robert G. Rassp, Editor-In-Chief of Rassp & Herlick

DISCLAIMER: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and are not those of the California Department of Industrial Relations, the Division of Workers’ Compensation, or the Workers’ Compensation Appeals Board. This article is not intended to serve as a legal brief or to provide legal advice and counsel are advised to consult with their own resources in researching specific issues that may arise in cases involving employee leasing.

INTRODUCTION

What are professional employer organizations, “PEOs?” Are employee leasing agreements and labor contracts valid in California? How does workers’ compensation insurance coverage work in employee leasing agreements? Who pays when a leased employee gets injured on the job? Are these like a shell game or peeling an onion? How does an attorney conduct discovery in these cases? Can employment be created by contract and not just under the Borello[1] factors?

This article is a journey through the creation of PEOs, how they are used in industry and what discovery counsel need to conduct in order to prosecute and defend these cases. Before you read on, you might want to read the case of Miceli v. Jacuzzi (2006) 71 Cal. Comp. Cases 599 (WCAB en banc decision). This case was originally referred to as the “Remedy-Temp” case, one of the earliest cases involving leased employees, and if you read this case and its earlier decisions your head will spin. Wait until you complete this article and you will understand that happened. By the way, the Miceli case started with a finger injury. Twenty years ago, Miceli was a big headache for DWC Assistant Chief Mark Kahn and Judge Robert Hjelle. PEO cases continue to vex the workers’ compensation legal community with everyone pointing fingers at one another. Hopefully this article will shed some light on the confusion.

WHAT IS A PEO OR EMPLOYEE LEASING COMPANY?

A PEO, or professional employer organization, is a business entity that hires out employees to specific companies or clients of the PEO to perform work at the customer or client location. Think in terms of one company leasing its employees to another company. Employee leasing occurs in many industries where the number of employees fluctuate based on operational demand within those industries. PEOs got their start in the entertainment industry—in movie and television production.

For example, it is not unusual for a movie production to ramp up the number of employees during the production period of filming scenes at a studio and on location. Many movie or television productions by Disney, Universal Studios, Sony Pictures and even independent production companies will hire a set of core employees who work in the various production fields, from talent to camera operators, to set builders to production assistants, etc.

Some of these employees would work on a movie or T.V. production side by side with temporary employees who receive payroll from Entertainment Partners (EP) or Cast & Crew Entertainment (C&C). The employees working under EP or C&C would not be the employees of the production company, but they would work out of the same union shop that the production company employees work from with the same pay, retirement benefits, hours, and other employee benefits. The difference is that the EP and C&C employees would end their relationship at the conclusion of the TV or movie production and would move on to other entertainment production projects by any other production company. It is not unusual for hair and make-up artists, set makers, production assistants, gaffers, camera operators, etc. to have 30-40 employers during a 30-year career in the entertainment industry due to the outsourcing of skilled workers from major production companies as a result of employee leasing agreements.

The practice of employee leasing expanded over the last thirty years to include other industries such as agriculture (farm labor agreements), logistics, construction trades, warehousing-distribution centers, garment industry, and manufacturing. There are many PEOs in existence due to the Ports of San Pedro and Long Beach where hundreds of thousands of loads from ships are placed on trucks and sent to the Inland Empire for placement on railroads and sent to other interstate trucking distribution centers. The number of employees along the logistics supply chain varies and is amenable for PEO employee leasing agreements to proliferate. See Labor Code section 2810.

In the construction trades as well, there are many PEOs within a specific trade—examples include Barrett Business Services, Inc., Roto Rooter plumbing franchisees, and other companies that combined specific trades with union and non-union shops.

INSURANCE COVERAGE FOR PEOs

Many PEOs have a high deductible workers’ compensation insurance policy which becomes a problem if premiums are not paid, money is diverted to shell companies under a “employer service agreement” between a PEO and a middleman company, such as a human resources administrator, or the PEO declares bankruptcy. One must bear in mind that workers’ compensation insurance is one of the most highly regulated forms of insurance in the State of California.

In order to fully understand PEOs, you must first understand the statutory mandate for employers to have coverage for workers’ compensation liability. Labor Code Section 3700 provides three ways for an employer to have coverage for workers’ compensation. The first way to comply with Section 3700 is to have an insurance policy of workers’ compensation issued by an insurance company pursuant to the Insurance Code and Title 10 of the California Code of Regulations. The second way to comply with Section 3700 is for an employer to obtain a certificate of self-insurance approved by the Director of the Department of Industrial Relations (DIR). The third way to comply with Section 3700 is to obtain permission from the DIR Director to self-insure by public entities, including joint powers authorities (such as school districts or utilities). A fourth way to be “covered” for workers’ compensation liability is to be “legally uninsured.” The only employer that is allowed to be legally uninsured for workers’ compensation liability is the State of California and its sub-agencies.

Labor Code Section 3701.9 prohibits PEOs and employee leasing organizations from being self-insured as of January 1, 2013. A certificate of consent to self-insure that had been issued to a PEO was revoked as of January 1, 2015. The reason this legislation was enacted is because many PEOs did not have sufficient funds to pay for workers’ compensation claims even though they had obtained a certificate of self-insurance under Section 3700(b).

GENERAL-SPECIAL EMPLOYERS

What is the legal basis for PEOs and employee leasing companies? Counsel must refer to Labor Code Section 3602(d)(1) which governs general and special employees. This section must be read together with Insurance Code Section 11663.

Labor Code Section 3602(d)(1) states:

For the purposes of this division, including Sections 3700 and 3706, an employer may secure the payment of compensation on employees provided to it by agreement by another employer by entering into a valid and enforceable agreement with that other employer under which the other employer agrees to obtain, and has, in fact, obtained workers’ compensation coverage for those employees. In those cases, both employers shall be considered to have secured the payment of compensation within the meaning of this section and Sections 3700 and 3706 if there is a valid and enforceable agreement between the employers to obtain that coverage, and that coverage, as specified in subdivision (a) or (b) of Section 3700, has been in fact obtained, and the coverage remains in effect for the duration of the employment providing legally sufficient coverage to the employee or employees who form the subject matter of the coverage. That agreement shall not be made for the purpose of avoiding an employer’s appropriate experience rating as defined in subdivision (c) of Section 11730 of the Insurance Code.

Labor Code section 3706 states, in essence, that if an employer is willfully uninsured and has not complied with the mandate for coverage for workers’ compensation liability under Labor Code Section 3700, any injured employee may elect to sue the employer for damages in tort under the theory of negligence per se—violation of Labor Code Section 3700 to have coverage for its employees.

Counsel must read Labor Code Section 3602(d)(1) together with Insurance Code Section 11663:

As between insurers of general and special employers, one which insures the liability of the general employer is liable for the entire cost of compensation payable on account of injury occurring in the course of and arising out of general and special employments unless the special employer had the employee on his or her payroll at the time of injury, in which case the insurer of the special employer is solely liable. For the purposes of this section, a self-insured or lawfully uninsured employer is deemed and treated as an insurer of his or her workers’ compensation liability.

In other words, liability for workers’ compensation benefits follows payroll. As will be discussed below, counsel MUST always establish who paid the injured worker because payroll is the hallmark of liability. Establishing payroll is not straightforward in every case—there are some PEOs who pay the leased employee their net pay while another entity that has a “employee leasing service agreement” with the PEO who pays the payroll deductions, or vice versa. This process can be a shell game or like peeling an onion to figure out who is liable for workers’ compensation benefits. Proper discovery in the event of an injury of a special employee is essential to the prosecution and defense of workers’ compensation cases involving a general and special employer. Counsel must join everyone—the PEO, its employee leasing service companies, the special employer, and all of the insurance companies for each entity, if any.

Sometimes counsel will see in documents obtained from a PEO or employee leasing company a typical lease that covers employees who are leased but who work for a special employer that may have operations in many states, including California. There are many entities that use the term, “LCF” which means “Leased Coverage for…” So “XYZ Employee Leasing, Inc. LCF Taco Bell #150” means that some or all employees who work at that Taco Bell location are paid by XYZ Employee Leasing Company as the general employer and are covered by XYZ’s workers’ compensation insurance policy. Taco Bell #150 is the special employer and would be listed on the XYZ Policy Information Page (the Declarations) and WCIRB forms as the covered special employer. XYZ’s policy would only cover the employees who work at Taco Bell #150 who receive payroll from XYZ Employee Leasing Company. If Taco Bell #150 had its own employees who receive payroll directly from Taco Bell #150, then those employees would have to be covered by an insurance policy issued strictly for those employees who received payroll directly from Taco Bell #150. So the special employees of Taco Bell #150 are the ones who are paid by XYZ Employee Leasing, Inc. Counsel has to get the nomenclature clear in their minds in order to understand the contractual relations between a general employer and a special employer.

RULES OF THE ROAD IN EMPLOYEE LEASING AGREEMENTS

There are some basic rules involved in determining liability for workers’ compensation benefits in a case involving a PEO or under an employee leasing agreement. First, general and special employers must have a written contract. The general employer provides payroll to the special employee. The general employer provides workers’ compensation insurance coverage for the special employee. The special employer’s workers’ compensation policy does not cover its special employees because the general employer’s does. Liability for workers’ compensation follows payroll per Insurance Code Section 11663.

Since many cases before the WCAB involve the issues of employment, employee leasing agreements, insurance coverage, and liability under a workers’ compensation insurance policy, a discussion of the business of workers’ compensation is necessary.

PAYROLL AND JOB CLASSIFICATION DRIVES PREMIUMS[2]

It should be noted at this point that premiums for workers’ compensation insurance coverage are based on two things—payroll and job classification. Remember, insurance premiums are based on risk of loss. For example, a construction worker will require a higher insurance premium than an office clerk. When a company obtains workers’ compensation insurance coverage, it is required to pay a deposit premium that is determined by the number of employees, their job classifications, and the amount of payroll. At the end of a month, quarter, half a year, or year, the employer’s payroll is audited by the insurance company’s underwriting department, and the ultimate premium owed is calculated, billed, and paid.

GENERAL PROVISIONS OF WORKERS’ COMPENSATION INSURANCE POLICIES

A workers’ compensation insurance policy is automatically renewed every year unless it is non-renewed by the insurance company, or cancelled due to non-payment of premium by the employer, or the employer terminates the policy for business reasons or changes insurance companies. Premiums can be increased due to the experience modification which is based on the claims history and claims costs for the employer’s past history.

Workers’ compensation insurance policies are unrestricted unless there is an exclusionary endorsement submitted through the WCIRB (Workers’ Compensation Insurance Rating Bureau[3]) to the State of CA Insurance Commissioner for approval. A basic rule of workers’ compensation law is that a special employer has joint and several liability for workers’ compensation benefits of its special employees if the general employer flakes out and does not cover a special employee’s alleged work injury. There is one big exception to this rule. A special employer is not liable for its special employees if there is an exclusionary endorsement on the special employer’s workers’ compensation policy for its non-special employees. In order to fully understand this crucial exception to liability, counsel should become familiar with the discovery necessary to prosecute or defend cases involving general-special employers.

Remember, workers’ compensation insurance policies are one of the most heavily regulated forms of insurance in existence. Counsel must refer to Insurance Code Sections 11650-11664. The relevant Insurance Code sections are in the “Blue Book” or “Workers’ Compensation Laws of California,” 2022 edition (LexisNexis). Title 10 Cal. Code of Regulations sections 2218 and 2250 through 2259 implement those Insurance Code Sections. Title 10 of the California Code of Regulations (CCR) are not in your Blue Book but can be found on line since Barclays allows public access to the CA Codes of Regulations.

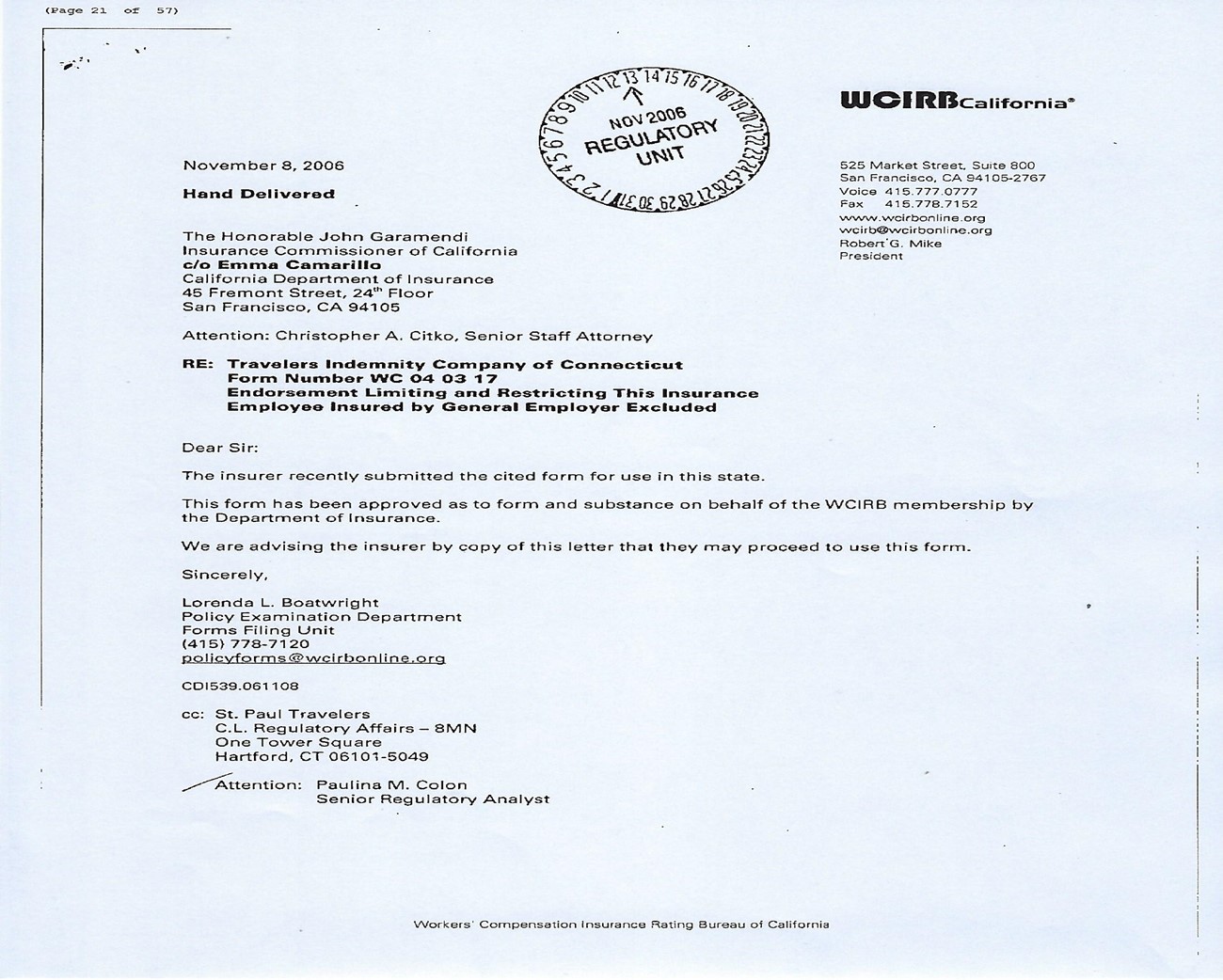

Title 10 CCR 2259 allows use of limiting and restricting endorsements of workers’ compensation insurance policies. Specifically, section 2259(a)(7) allows a policy “To exclude liability of an employer for employees who are covered under another employer’s workers’ compensation policy pursuant to an agreement made under Labor Code Section 3602(d).” Section 10 CCR 2266 mandates any restrictive endorsements to a workers’ compensation policy be submitted to the rating organization (WCIRB) and not to the Department of Insurance for approval. The WCIRB submits restrictive endorsements to the Insurance Commissioner for approval. The law changed effective in 2016 that mandates Insurance Commissioner approval of restrictive endorsements but the request for approval must be made by an insurance company’s underwriting or government relations department through the WCIRB.

The regulations separate routine amendments to workers’ compensation policies from requests for approvals of restrictive endorsements. In accordance with Title 10 CCR 2251 and 2254, the WCIRB submits to the Insurance Commissioner any non-standard policy forms, endorsement forms, or ancillary agreements, and the Insurance Commissioner has 30 days to deny the endorsements; otherwise, silence means approval. In contrast, as discussed above, Section 10 CCR 2259 specifically allows for restrictive endorsements, but they have to fall under subsections 2259(1) through (10) and be submitted by the WCIRB for approval by the Insurance Commissioner.

WHAT IS IN AN UNDERWRITING FILE?

In order for counsel to understand the discovery process in cases involving insurance coverage, PEOs, and employee leasing agreements, it is necessary to learn about what to look for in an insurance company’s underwriting file.

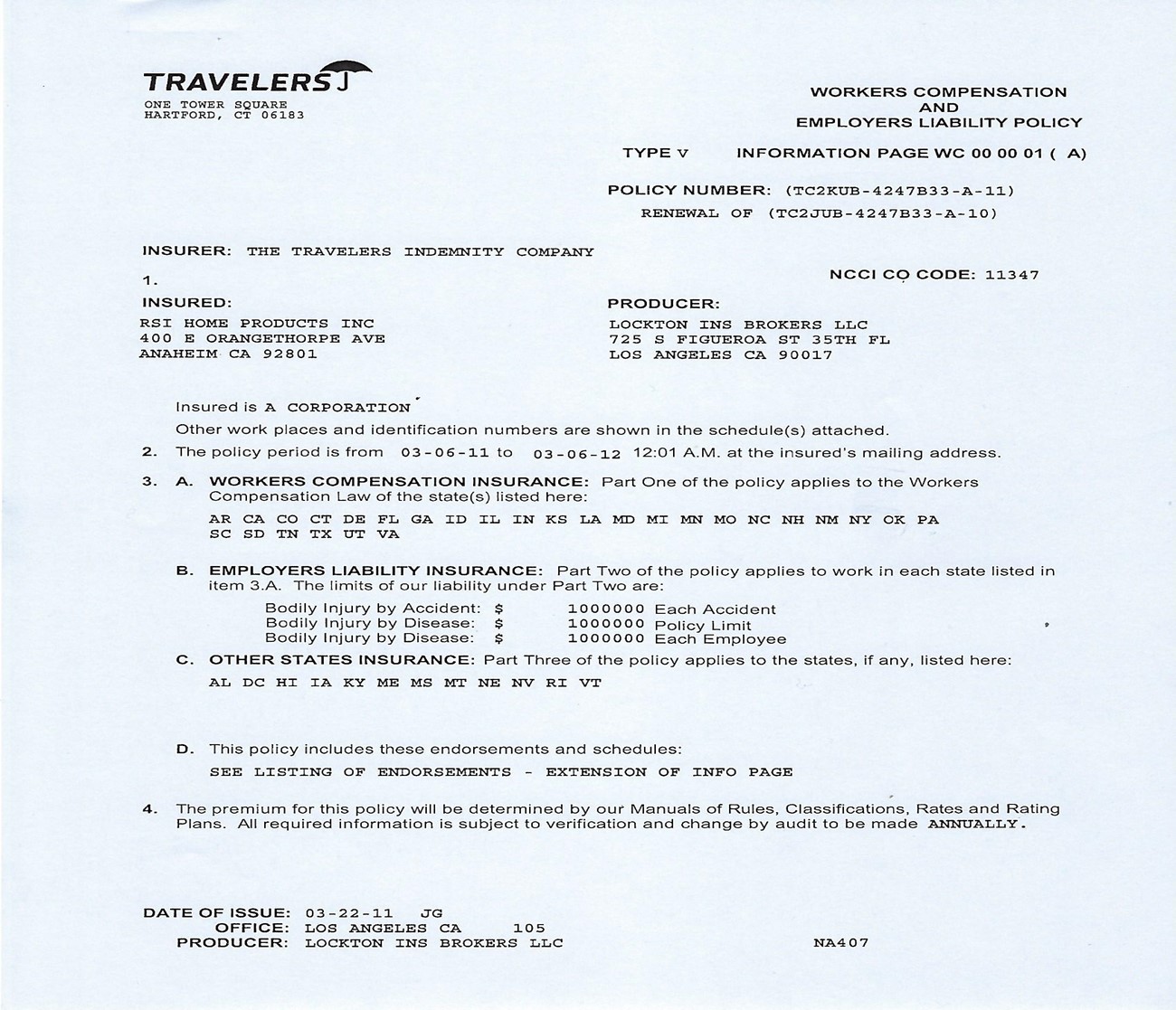

The first document to look for is the “Information Page” or Declarations of a workers’ compensation insurance policy. The examples of documents given in this article are a public record and are taken from a published arbitration decision that is a Noteworthy Panel Decision in the LexisNexis database. Most insurance policy’s Information Page actually consists of hundreds of pages that constitute the entire insurance policy that is specifically issued to an employer.

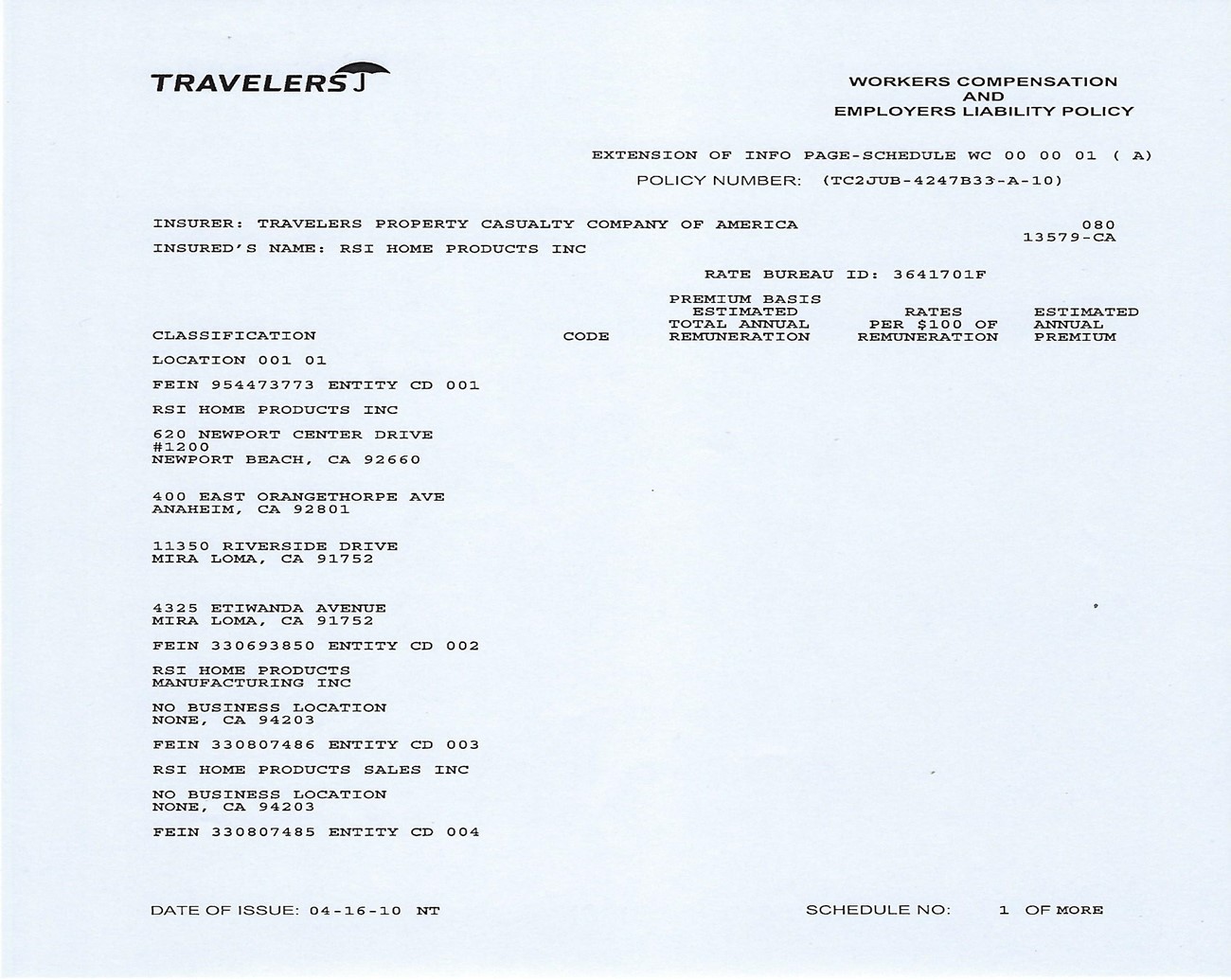

The example discussed here involves a company called “RSI Home Products” hereinafter called “RSI.” RSI manufactures wood cabinets for kitchens and bathrooms. They have operations in 28 states and have at least three locations within California. RSI was insured by Travelers Property Casualty Company of America for its regular employees in California.

RSI Products entered into an employee leasing agreement pursuant to Labor Code Section 3602(d)(1) with Select Staffing, a PEO. Select Staffing had two policies—one with Kemper and another one with Ace American Insurance Company.

Some RSI employees were listed under the Kemper policy, as Select Staffing was a PEO general employer with a contract with RSI as a special employer. Select Staffing was the general employer who agreed in a written contract to provide payroll and workers’ compensation insurance coverage for some people who were assigned by Select Staffing to work at RSI Products locations in California.

The employees paid by Select Staffing who worked at RSI Products were special employees of RSI Products. RSI Products did not pay payroll to the special employees who worked at their California locations because Select Staffing did. So employees of Select Staffing worked side by side with employees of RSI Products. Also, the ACE American policy with Select Staffing did not list RSI Products under their policy.

The examples below are part of the record in the case of Lorenzo Toscano Corona v. Koosharem dba Select Staffing, (RSI Home Products), 2016 Cal. Wrk. Comp. P.D. LEXIS 542 (Appeals Board noteworthy panel decision).

Here is an example of an Information Page or “Declarations Page”:

This policy was incepted on March 6, 2010 and automatically renewed annually every March 6 thereafter until cancelled. Paragraph 3A is always one of the most important provisions in any workers’ compensation insurance policy because it shows which states RSI has coverage by Travelers for its employees who work in those listed states.

Paragraph 3B shows the maximum policy limit is $1,000,000 for each accident, each disease, and each employee. Insurance companies will obtain their own separate policy to cover losses above the $1,000,000.00 policy limits and that insurance product is called “Reinsurance.” Liability for workers’ compensation benefits is not capped and, in catastrophic cases, Travelers would have to pay benefits even if liability exceeds the policy limit.

Employers provide compliance with Labor Code Section 3700 by having a minimum policy like this one with Travelers, but Travelers would pay benefits if its liability exceeds the $1,000,000 policy limit—any amount of liability over $1,000,000 in a case would be paid by Travelers through a reinsurance policy it obtained separately. Self-insured employers can also obtain reinsurance policies that cover losses greater than what their self-insured limit was established (also usually $1,000,000 per loss).

Paragraph 3C, “Other State’s Insurance” means if an RSI employee works at one of the states listed in this paragraph, their injuries would be covered under those state’s workers’ compensation system but excludes monopolistic fund states, such as Washington State or the other 13 NCCI[4] states. This paragraph is included in a standard policy in case RSI decides to open new operations in a state where it has not yet conducted business.

The Information Page actually includes many additional pages. In this case, the underwriting file for this Travelers policy was over 2,000 pages with the Information Page actually consisting of over 250 pages.

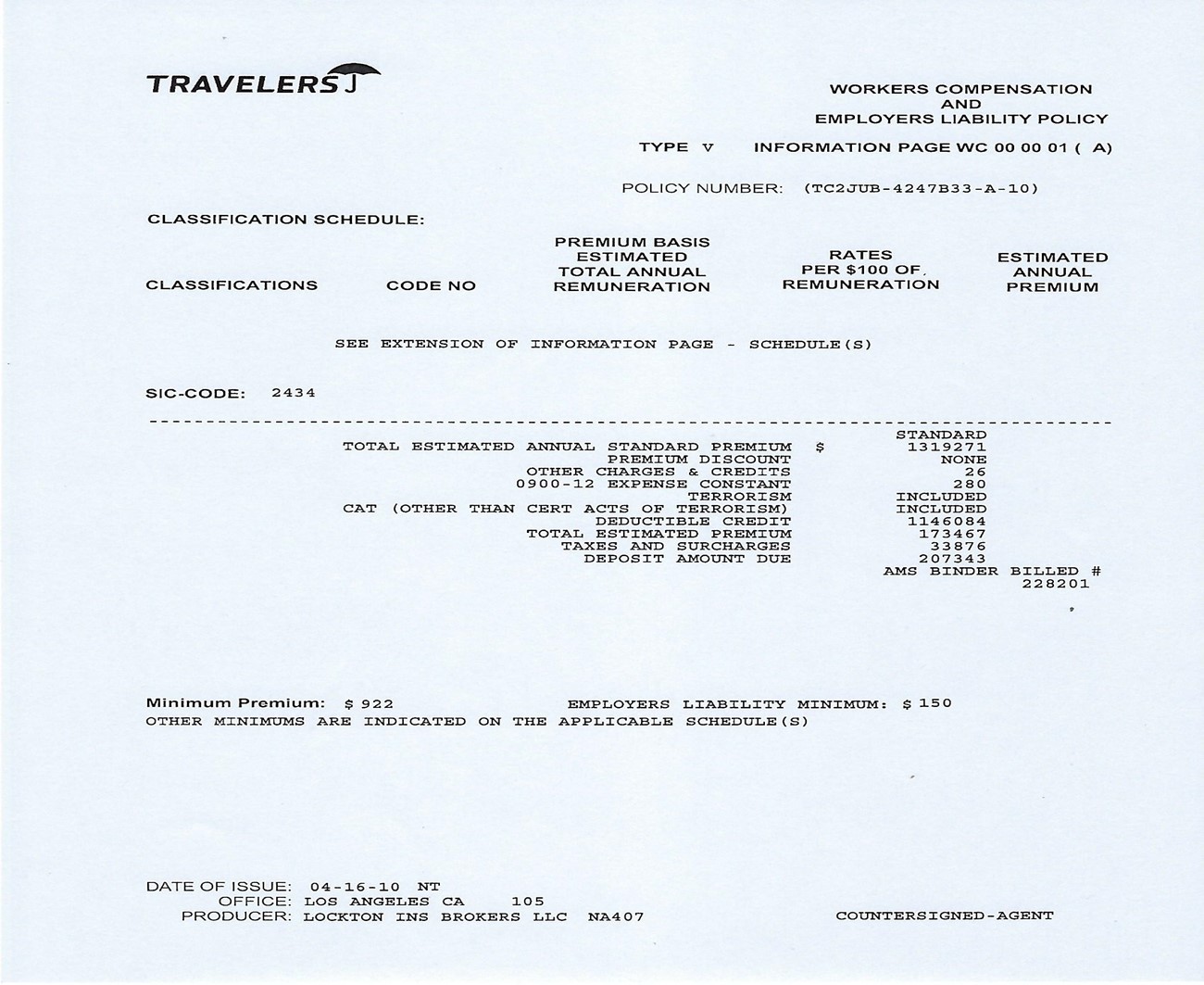

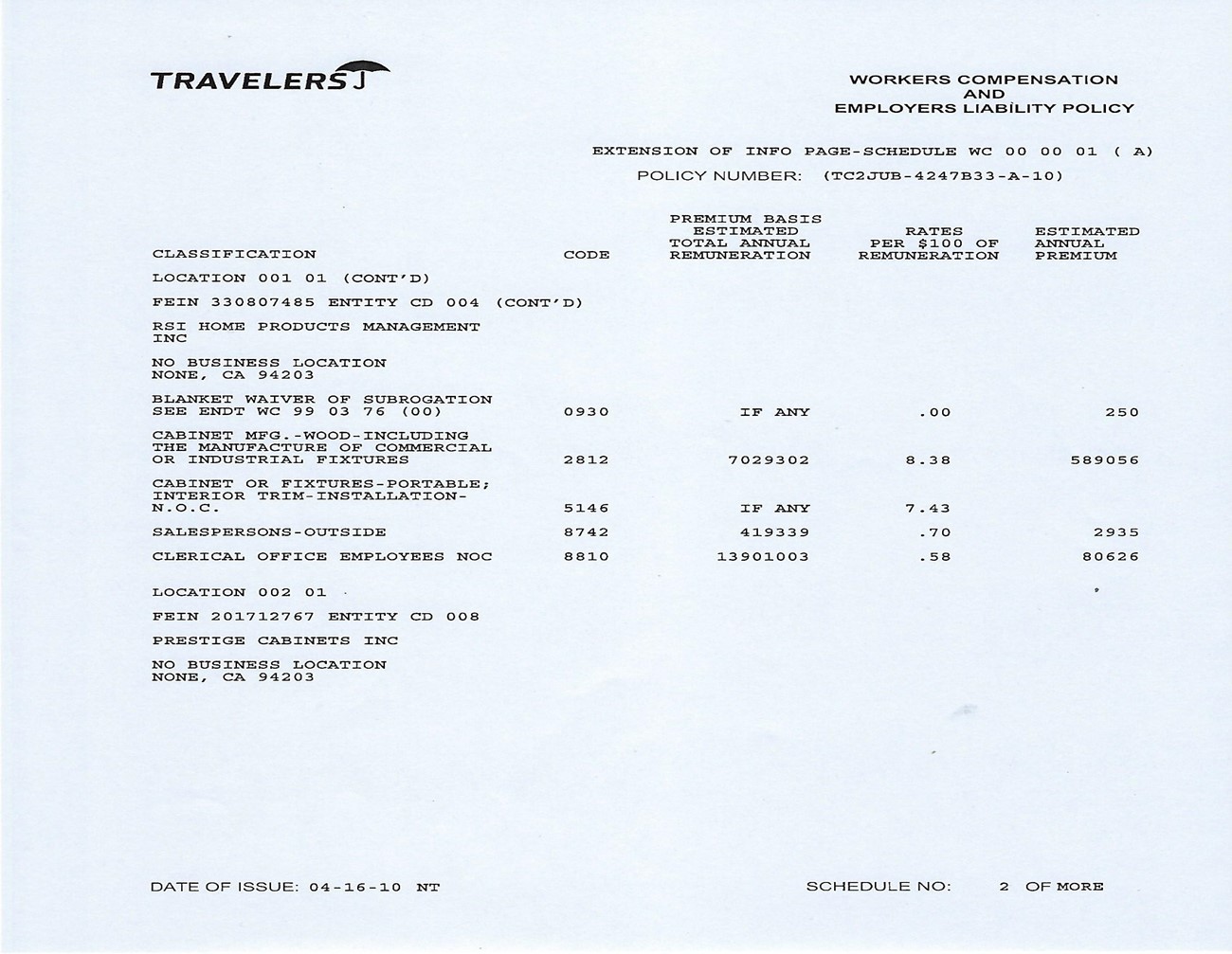

The second page of the Information Page shows an estimated premium for the RSI policy with Travelers, based on prior payroll and job classifications. RSI had rough carpenters, finish carpenters, outside sales staff, and office staff. Since this was a renewal of the policy, Travelers and RSI had a good idea of what the following year’s payroll would be, along with job classifications. For renewal of this policy for policy period March 6, 2011 to March 6, 2012, Travelers calculated a premium deposit of $207,343.00. At the end of each policy period, Travelers would audit RSI’s payroll and job classifications in order to bill them for a final annual premium.

This page shows the physical locations of RSI operations in California, along with columns that show the estimated payroll, rating of job classification premium per $100.00 of wages, and the estimated premiums for each classification of jobs performed. At the end of the policy year, RSI would complete a payroll report that captures the actual payroll for each job classification so that Travelers could calculate the actual premium due for the previous policy period. Again, the payroll reports could be due annually, semi-annually, or monthly depending on the terms of the insurance policy. Payroll reports also usually have each employee’s name, social security number, job classification, and total payroll amount for a given period of time. All of this information is discoverable during litigation at the WCAB or in arbitration proceedings.

This page shows the estimated payroll of $7,029,302.00 in wages paid for rough carpenters who make the wood cabinets, with a premium of $8.38 per $100.00 of wages or the total estimated premium of $589,056.00. Finish carpenters are rated at $7.43 per $100.00 of wages with no estimate of total wages; outside sales employees estimated wages are $419,339.00 for a premium of $.70 per $100.00 wages of $2,935.00; and clerical office staff of $13,901,003.00 in wages for a premium of $.58 per $100.00 wages of $80,626.00.

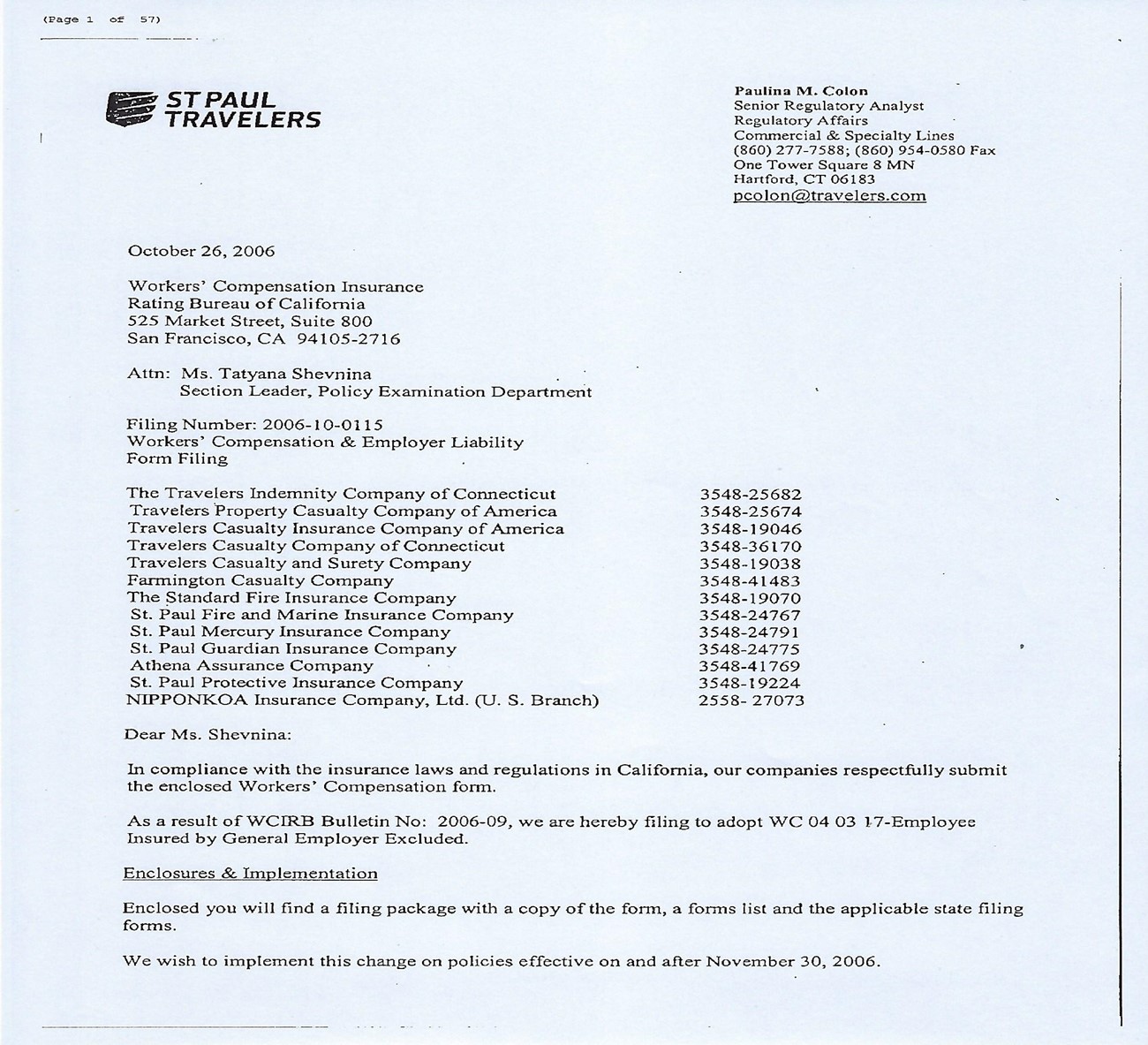

The next two pages, shown below, is a letter from Travelers’ Government Affairs representative to the WCIRB requesting permission from the State of CA Department of Insurance through the WCIRB to allow an exclusionary endorsement of employees who work at RSI locations, are paid by Select Staffing, and are covered by a general employer-special employer agreement pursuant to Labor Code Section 3602(d)(1). Select Staffing had Kemper Insurance Company provide insurance coverage for the Select Staffing employees who worked at RSI locations in California.

This letter was a crucial piece of evidence submitted at arbitration proceedings where CIGA claimed there was “other insurance” pursuant to Insurance Code Section 1063.1(c)(9). This exclusionary endorsement prevented Travelers from having liability in a case involving an employee of Select Staffing who was injured while working at an RSI facility in California. The details of this case are discussed below.

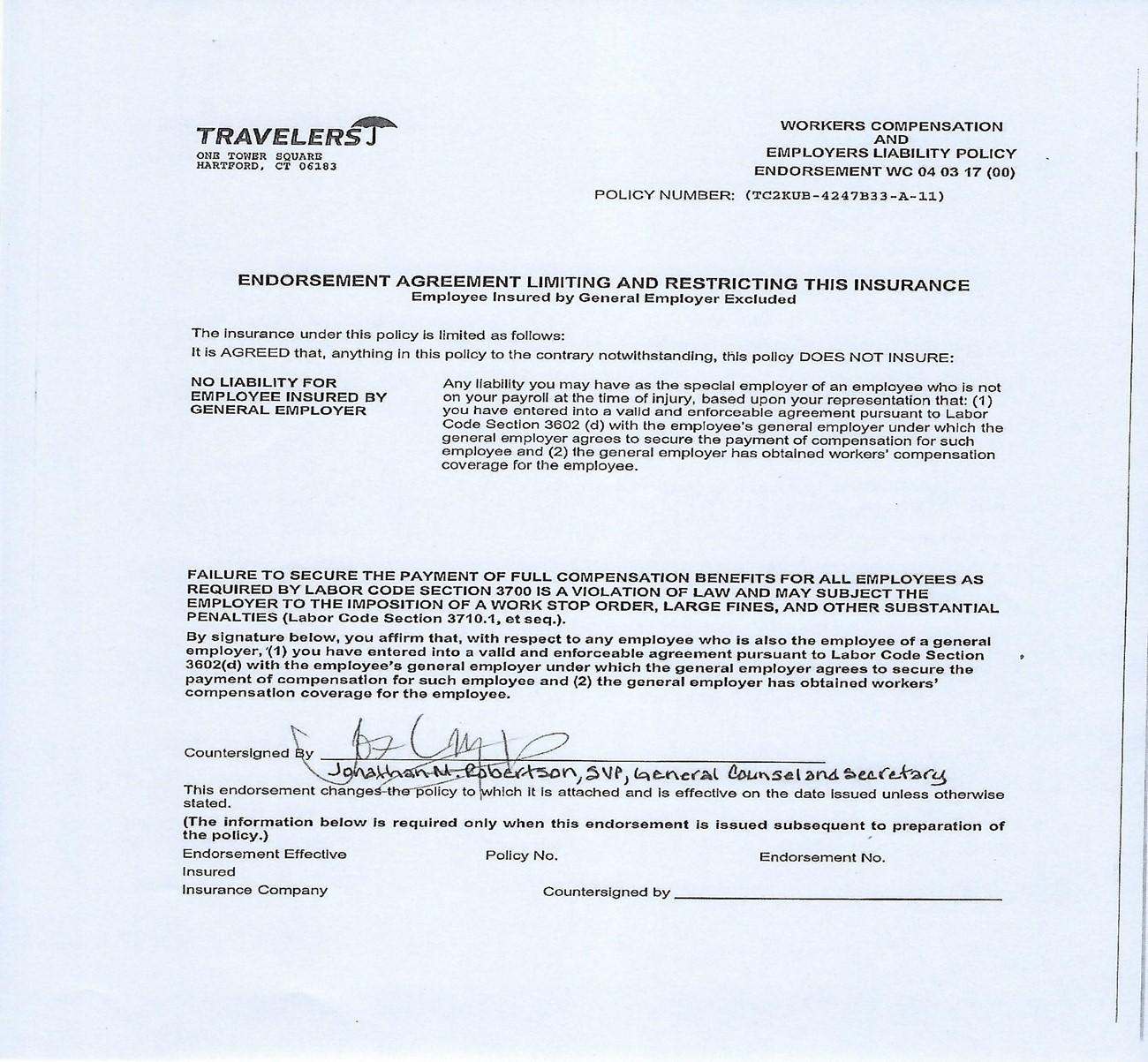

This is what an exclusionary endorsement for general-special employees looks like. Notice that this Endorsement specifically cites the language in Labor Code Section 3602(d)(1). This endorsement also warns Travelers that if Select Staffing does not secure workers’ compensation insurance coverage for RSI’s special employees, then Travelers would be liable despite having this exclusionary endorsement. In fact, Select Staffing did secure coverage by Kemper for RSI’s special employees at the time this exclusionary endorsement was approved. However, trouble occurred later when Kemper was declared insolvent, and liquidated, and its pending claims were taken over by CIGA.

This is a letter from the WCIRB to the Insurance Commissioner indicating that the WCIRB has approved the exclusionary endorsement for Travelers that excludes workers’ compensation insurance coverage for RSI’s special employees who are insured under the PEO Select Staffing’s general employer policy with Kemper. Everything is fine until Kemper went insolvent and CIGA took over its claims.

APPLICATION OF RULES GOVERNING PEOs AND EMPLOYEE LEASING

There are some basic rules for counsel to follow involving PEOs, employee leasing agreements, and workers’ compensation insurance coverage.

- Workers’ compensation insurance policies are automatically renewed every year unless cancelled by the insured or insurer (for non-payment of premium, employer misrepresentations, or the insurer decides not to insure the type of business). Ins. Code section 676.8.

- “Employment” between the injured worker and the special or general employer is a different analysis under Borello than “Employment” for insurance coverage purposes. See G. Borello & Sons, Inc. v. Department of Industrial Relations (1989) 48 Cal. 3d 341, 50 Cal. Comp. Cases 80.

- “Employment” for insurance coverage purposes can be created by contract between entities.

OWNER CONTROLLED INSURANCE PROGRAMS (OCIP)

Do not confuse PEOs and employee leasing agreements pursuant to Labor Code Section 3602(d)(1) with OCIPs (Owner Controlled Insurance Programs). An OCIP involves an agreement where a general contractor carries workers’ compensation coverage for all employees of its own employees and all employees of the sub-contractors who work on a site-specific project.

These OCIP agreements usually involve public works projects or large developments. Some examples of OCIP agreements include the development of the Metropolis twin 51 story mixed use buildings in downtown Los Angeles, the San Diego Convention Center, and the Purdue single-family development project in the City of Santa Clarita.

All sub-contractors in an OCIP project must have their own workers’ compensation insurance coverage for its own employees regardless of where they work. Payroll for the sub-contactor’s employees are backed out of the premium calculations for the sub-contractor’s own policy, and the payroll is transferred for calculation for the premiums paid by the OCIP general contractor. Usually the master workers’ compensation insurance policy for the general contractor that covers all sub-contractor employees involves a different insurance carrier from the ones that insure the sub-contractor companies.

An important note is appropriate here: when counsel obtains WCIRB records of large development companies, sometimes many different insurance companies will appear on a WCIRB list for a specific period of time. Each insurer is not listed as an OCIP policy so counsel has to look further to determine which policy is the insurance policy for the general contractor and only covers the general contractor’s own employees as opposed to policies that are strictly site specific and cover a large development project, including employees of the general contractor plus all of the sub-contractor’s employees who work at a specific site.

DISCOVERY IN PEO AND EMPLOYEE LEASING CASES

Cases involving PEOs and employee leasing arrangements create a nightmare for counsel who is not familiar with the proper discovery necessary to prosecute or defend them. The first question Applicant’s attorneys need to ask in every case is who paid the Applicant their payroll on the alleged date of injury? Remember, Insurance Code section 11663 says liability for workers’ compensation benefits follows payroll. Applicant’s counsel at intake should obtain from the injured worker payroll stubs, W-2 forms, US Treasury Form 1099, and even income tax returns. Many PEOs will have more than one entity involved in providing payroll to employees, including at times “middleman” or intermediary companies. In fact, there have been cases where the general employer pays the general employees their net pay per pay period and another company pays the payroll taxes. That is exactly what occurred in the Serrano case discussed below.

Counsel needs to obtain the underwriting file for the general employer’s and special employer’s respective workers’ compensation insurance policies. Issuing subpoenas for the claims file will not get you there! Usually the claims department is completely separate from an insurance company’s underwriting department and, in many situations, a claims professional may not even have access to an underwriting file. When a claim is filed, the only thing a claims professional needs to do is to confirm with the underwriting department that the employer’s policy is in effect and was not cancelled on the alleged date of injury. That is the extent of the claims examiner’s contact with an underwriting department.

Counsel should obtain the following documents from the underwriting files for the general employer and special employer:

- Application for workers’ compensation insurance The application will contain valuable information about the company seeking insurance coverage—what the company does, what locations the employees will work at, what type of product or service is provided, whether employees travel out of state, and the types of jobs that are to be covered by the policy plus an estimated payroll for each job.

- Information Page. What does Information Page say? (They are standardized throughout the country.)

- Exclusionary endorsements. Are there any exclusionary endorsements? If so, how do they affect coverage for the Applicant’s alleged injuries?

- Correspondence with Insurance Commissioner or WCIRB. Look for letters to or from the Insurance Commissioner or to WCIRB from the general and special employer’s insurance company, respectively, requesting an exclusionary endorsement from the inception date of the policy through the alleged date(s) of injury claimed by the Applicant.

- Have there been any amendments to the policy since its inception?

- Notices of cancellation. Are there any notices of cancellation of the policy? If so, when and was the policy reinstated and, if so, when?

- Payroll reports. Look for payroll reports for years the alleged injured worker was employed there.

- Written contracts between general employer and special employer. Obtain the written contracts between the general employer and the special employer.

- Contract between PEO and any company claimed to be part of PEOs “service agreement.” Obtain any contract between the PEO and any company claimed to be part of the PEO’s “service agreement.” Simply put, subpoena contracts between the general employer and special employer and any intermediary companies. Many intermediary companies have names with the term “Human Resources” or “HR” embedded. Sometimes these intermediary companies are owned by the same people or company that own the PEO. Sometimes a PEO itself has the term “HR” in its name. This is where counsel has to peel the onion, and name every entity along this chain from the general employer to the intermediary companies, if any, to the special employer.

- SDT payroll records/personnel file for the injured worker from the general employer AND the special employer. Sometimes, injured workers work for a PEO or employer leasing company at different times, e.g., during a “try-out” period they may work first for the general employer, and then, the special employer at some point later directly hires the person. If the employee files a cumulative trauma injury claim, counsel would have to name both the general and special employer and their respective insurers.

- Statutory material. Also, counsel is strongly advised to read Labor Code Section 5500.5(a) that determines liability for workers’ compensation benefits in a cumulative trauma claim if there is a gap in insurance coverage by an employer (general or special) along the period of injurious exposure. So liability for the entire cumulative trauma injury may fall on one insurance company that had coverage during any period of employment the injured employee worked for the general or special employer.

- Copies of payroll reports sent the year of the injured worker’s alleged injury. If it is a cumulative trauma, then the last year of injurious exposure if there is insurance coverage, or the portion of insurance coverage during any period of injurious exposure.

- Counsel should also consider deposing the PMK for the policy (usually the insurance company’s underwriting manager).

CASE LAW PERTAINING TO PEOs AND EMPLOYEE LEASING

The discussion of case law here will get counsel started on understanding how the Appeals Board and Courts of Appeal have developed decisional law pertaining to employee leasing and liability for workers’ compensation benefits.

When an employer lends an employee to another employer and relinquishes to the borrowing employer some right of control over the employee’s activities, a ‘special employment relationship’ arises between the borrowing employer and employee.” Caso v. Nimrod Productions (2008) 163 Cal. App. 4th 881, 888-889; March v. Tilley Steel Co. (1980) 26 Cal. 3d 486 [45 Cal. Comp. Cases 193] (“Marsh”); Kowalski v Shell Oil Co. (1979) 23 Cal. 3d 168 [44 cal. Comp. Cases 134] (“Kowalski”).

A special employer is liable for an injured employee for workers’ compensation benefits, and the determination of whether a special employment relationship exists is a question of fact. Ibid.

A general and special employment relationship can be established by contract between a general employer and a special employer. See Labor Code Section 3601(d)(1); Jesus Felix Serrano v. Exact Staff (2016) 81 Cal. Comp. Cases 777 (writ denied); Lorenzo Toscano Corona v. Koosharem dba Select Staffing, 2016 Cal. Wrk. Comp. P.D. LEXIS 542 (Appeals Board noteworthy panel decision). The Serrano case specifically indicates that employment can be created by contract for the purposes of insurance coverage and liability for workers’ compensation benefits.

In Serrano, the Applicant was employed through a general employer, Exact Staff, which entered into two contracts. The first contract was with the special employer, Service Connection, where the Applicant actually performed duties as a warehouse worker and where Applicant sustained injuries when crashing a forklift. The other employment was with HR Comp, a human resources management company that had a service agreement as a PEO with Exact Staff. The general employer, Exact Staff, paid the Applicant their net payroll. HR Comp paid the payroll taxes to the state and federal government, and also paid workers’ compensation premiums to Travelers which insured HR Comp. Here, the general employer Exact Staff delegated its duty under Labor Code Section 3602(d)(1) to the PEO HR Comp to carry workers’ compensation insurance coverage for the special employees of Service Connection.

Litigation among Exact Staff, HR Comp, and Service Connection occurred over insurance coverage and workers’ compensation liability for Applicant’s injury from the forklift accident. In addition, Travelers contended that its policy with HR Comp was procured by fraud and misclassification since the policy was obtained on line and HR Comp represented in the application for insurance that it had one clerical employee when, in fact, it covered payroll deductions for 50 warehouse workers.

The arbitrator[5] held that HR Comp was an employer of the Applicant that was created by contract even though the Borello factors did not apply. So there was joint and several liability between the general employer Exact Staff, the intermediary payroll PEO human resources company HR Comp who paid the payroll taxes, and the special employer Service Connection where the Applicant actually worked. Counsel who defends or prosecutes PEO cases are strongly urged to read the Serrano case so that the understanding between the factual and legal aspects of PEO cases can be best understood.

The liability of general and special employers for compensation benefits is joint and several. Fireman’s Fund Indemnity Co. v. State Compensation Insurance Fund (1949) 93 Cal. App. 2d 408 [14 Cal. Comp. Cases 180]. This is the most important case on the issue of who is liable for workers’ compensation benefits in employee leasing cases. As counsel can see, the law has been well settled since 1949. The key is for counsel to obtain the contracts between the different entities to see who is the general employer and who is the special employer and whether any other entity is involved in providing payroll, or payroll deductions, and/or human resources services by contract. In many cases, like in Serrano, a PEO can be the general employer or an intermediary human resources company, and the special employer is the entity where the injured employee actually works.

Circling back to the RSI case example, the question presented in that case was whether Travelers who insured the employees of RSI, but not their special employees, had a valid exclusionary endorsement for RSI’s special employees (because Kemper insured those employees under Select Staffing’s general-special employer contract with RSI).

To properly exclude liability by way of an exclusionary endorsement and to exclude liability for an Applicant’s injuries under Form 04 03 17 (the current WCIRB form that is called an exclusionary endorsement under a general-special employer agreement—Select Staffing from our example above), an insurer for a special employer (RSI Home Products) must show:

- The insurer received approval to use the endorsement form from the Insurance Commissioner through the WCIRB;

- The special employer [RSI Home Products] entered into a valid and enforceable Labor Code Section 3602(d)(1) agreement with the general employer [Select Staffing]; and

- The general employer obtained workers’ compensation coverage for the excluded employees.

In this case, the general employer’s insurer (Kemper) went insolvent, and CIGA alleged there was “other insurance” in the form of Travelers [insurance for the special employer RSI] and ACE [the general employer’s insurer but for other special employers and not for special employer RSI Home Products]. The outcome of Lorenzo Toscano Corona v. Koosharem dba Select Staffing, 2016 Cal. Wrk. Comp. P.D. LEXIS 542 (Appeals Board noteworthy panel decision) was that Travelers had a valid exclusionary endorsement and ACE did not[6]. Therefore, upon the insolvency of Kemper (for the general employer Select Staffing), Travelers, as the insurer for the special employer RSI, was not “other insurance” since it had a valid exclusionary endorsement for RSI’s special employees. However, ACE’s insurance policy for Select Staffing was held to be an unrestricted policy and was “other insurance” under Insurance Code Section 1063.1(c)(9) and, thus, liable even though the ACE policy did not name RSI as a customer under Select Staffing’s PEO policy with ACE.

Counsel should read the Serrano case along with Lorenzo Toscano Corona v. Koosharem dba Select Staffing, 2016 Cal. Wrk. Comp. P.D. LEXIS 542 (Appeals Board noteworthy panel decision). Travelers had a valid exclusionary endorsement for RSI special employees, and ACE did not. ACE was considered “other insurance” under Insurance Code Section 1063.1, and Travelers got off the hook. ACE eventually took over defense of the Toscano Corona case, and settled the case in chief with the Applicant via a Compromise and Release for $30,000.00.

In any insurance coverage dispute, counsel should refer to the relevant statutes: Insurance Code Sections 11650-11660 which combined say that WC insurance policies are unrestricted and unlimited. Endorsements that limit or restrict coverage of WC policies are subject to prior approval by the Insurance Commissioner through the WCIRB. See Insurance Code Section 11657 and Title 10 Cal. Code of Regulations sections 2261 and 2262. Most importantly, insurance companies have the burden of proof that they have a restricted endorsement. Ibid.

See also Proulx Mfg. Co. v. WCAB (Bahney) (2010) 75 Cal. Comp. Cases 782 (writ denied). This case nicely parallels the facts in the Select Staffing/RSI Home Products case with the same result—the insurer for the special employer, Proulx, was considered “other insurance” pursuant to Insurance Code Section 1063.1(c)(9) when the insurer for the general employer, Allied, became insolvent and the California Insurance Guarantee Association had to take over any covered claims and seek reimbursement and liability from the special employer’s insurance company. In Proulx Mfg. Co. the special employer’s insurer did not have an exclusionary endorsement for their special employees. As a result, the special employer’s insurer had to reimburse CIGA and pay future benefits.

WHAT IF A PEO, INTERMEDIARY COMPANY OR SPECIAL EMPLOYER HAS NO WORKERS’ COMPENSATION INSURANCE COVERAGE?

There are many legitimate PEOs, employee leasing companies, and human resource administrative companies who assist special employers in handling payroll and other human resource services, especially for companies who have fluctuating operational needs or who do not want to pay their own employees for management of personnel.

However, there are also many unscrupulous companies that exist who do not play by the rules. Cases that arise out of these entities, where one or more of them are uninsured for workers’ compensation liability coverage under Labor Code Section 3700, result in prolonged litigation and delay of receipt of benefits. When a PEO, intermediary company, and/or special employer are willfully uninsured, then the provisions of Labor Code Sections 3710 through 3733 apply and the injured employee may pursue their action through the uninsured employer’s benefits trust fund program (UEBTF) upon proper joinder of them and the Office of the Director’s Legal Department (OD Legal).

There are many cases where some of the involved entities do have workers’ compensation insurance coverage while others don’t, and joinder of the UEBTF is still necessary so that the people who cause the uninsured status of an entity are held to answer, along with any substantial shareholders for that uninsured entity if it is a corporation.

WCAB TRIAL OR ARBITRATION OR BOTH?

In cases that involve a PEO, employee leasing contracts, and general-special employer relationships, the question arises: which forum is the proper one for litigation over issues involving these entities? When do you go to court, and when do you go to arbitration?

Many times, counsel will appear at a WCAB office and will ask for the presiding judge to refer the matter to mandatory arbitration pursuant to Labor Code Section 5275(a)(1) over insurance coverage or Section 5275(a)(2) right of contribution in accordance with Section 5500.5. Most of the time, arbitration is not the proper forum to litigate disputes between an Applicant and defendants that involve these entities. The determination must be made on a case-by-case basis. Each judge has the discretion to determine if a case stays at the WCAB for determination of who an employer is, or to refer the matter to the presiding judge at the district office having venue to order the matter into arbitration.

Insurance coverage is rarely in issue since a general employer will have their insurance coverage as required by Labor Code Section 3602(d)(1) and the special employer will have its own insurance coverage for its own employees. This picture gets muddled when a PEO has multiple insurers, its policy does not exist, or the PEO’s or general employer’s insurer goes into insolvency; or if there is an intermediate entity that has an employer service agreement with the PEO or employee leasing company; or if the special employer claims its policy has an exclusionary endorsement for its special employees. In the permutations of these relationships, it becomes obvious that confusion will occur about whether employment, coverage, and liability under a specific insurance policy are in issue and where this dispute should be litigated.

If employment is in issue, you have already learned that employment can be created under the Borello factors or by contract between these entities under the Serrano case. The issue of employment between the injured worker and these entities are under the direct jurisdiction of the WCAB and trial judges. The issue of liability for workers’ compensation benefits under a specific injury or cumulative trauma is also under the jurisdiction of the WCAB and its trial judges.

The issue of whether an insurance policy applies in a given case falls under mandatory arbitration since “insurance coverage” under Labor Code Section 5275(a)(1) can be interpreted to include whether there is liability under a policy. The best example of this is whether an insurance policy has an exclusionary endorsement that would result in a finding by an arbitrator that a policy excludes coverage for special employees who are paid wages by a PEO, employee leasing company, or intermediate entity, and wages are not paid directly by a special employer. Remember, by contract, special employers are paying for the services of a PEO or employee leasing company.

Therefore, cases involving PEOs, employee leasing agreements, and general-special employer cases should be first heard at the WCAB, and the issue of employment is to determined. Then the question of insurance coverage becomes an issue before an arbitrator: as to liability under a specific policy or coverage itself (e.g., if an insurer claims liability is excluded under a specific exclusionary endorsement).

If the parties have access to a sitting judge at the WCAB who understands these issues, the parties may be better off litigating all issues before the WCAB and save the expense of an arbitrator.

On the other hand, arbitrating employment, insurance coverage, and liability under an insurance policy may save time. So counsel needs to determine what is best for the parties and which forum will provide the quickest resolution of employment and insurance policy liability issues. Keep in mind that while these entities point their fingers at each other, an injured worker is probably not receiving workers’ compensation benefits while employment, insurance coverage, and liability issues are being litigated between a PEO, intermediary human resources-type company, and a special employer.

As stated earlier, in many cases, the special employer should step up and pay benefits if an injury should be otherwise admitted and the issue of exclusionary endorsement, liability of a general employer and/or intermediary companies could occur later in contribution proceedings. Remember, case law since 1949 mandates that general and special employers are jointly and severally liable for workers’ compensation benefits.

CONCLUSION

The law governing general and special employment can get complicated. Normally, employment is determined from the Borello factors in determining whether an injured worker was an employee or independent contractor of a hirer at the time of an alleged injury at work. When multiple layers of employment created by contract is added to the mix, complex litigation occurs, and parties need to be educated about the proper discovery that needs to be completed in order to establish liability for work injuries.

In many of these cases, the lack of understanding by counsel and their clients results in unnecessary delay of claims, including ones involving serious injuries to innocent workers. Counsel for every party involved in PEO and employee leasing cases have an affirmative duty to conduct proper and quick discovery in order to understand what entity or entities are liable for workers’ compensation benefits. Everyone has a duty to investigate, including attorneys for injured workers.

Most judges will place liability first on the special employer when the general employer has intermediary companies involved by so-called service agreements. This usually occurs when a general employer or PEO delegates its duty under Labor Code Section 3602(d)(1) to a human resource management company or other shell company.

Best practices exist when a general employer or its claims administrator refuses to pay a claim for a special employee who is seriously injured. The special employer’s insurer should pay the claim and then litigate in arbitration any contractual disputes that may exist for insurance coverage and liability by a general employer and any intermediate companies. Barring that, a special employer should immediately be contacting the general employer, its insurer, and the special employer’s own insurance claims department and the employer’s agent or broker to inform them of a work injury occurring to a special employee.

Applicant’s counsel must obtain payroll information from the injured worker in order to understand and apply Insurance Code section 11663 that establishes liability for workers’ compensation benefits follow payroll. That way, joinder of appropriate parties and their claims administrators and discovery can occur without any unnecessary delay.

The law of insurance coverage under a workers’ compensation policy and general-special employment situations are challenging and exciting parts of the practice of workers’ compensation law.

© Copyright 2022 Robert G. Rassp. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

[1] S.G. Borello & Sons, Inc. v. Department of Industrial Relations (1989) 48 Cal. 3d 341, 50 Cal. Comp. Cases 80. “Borello Factors” are: 1. Is the worker engaged in a distinct occupation or business? 2. Is the work specialized that the worker performed without supervision? 3. Does the worker exercise a special skill? 4. Who provided the tools and location for the work? 5. What is the length of time the worker performed the services? 6. Was the worker paid by time or by the job? 7. Was the work part of the hirer’s regular business? 8. Did the parties believe they were creating an employment or independent contractor relationship?

[2] This author wants to acknowledge and thank Don Knudsen, underwriting manager from State Compensation Insurance Fund, who on many occasions was an expert witness for SCIF who appeared before this author when this author was an arbitrator in insurance coverage cases involving SCIF. His knowledge and ability to explain complex insurance issues was invaluable.

[3] Every state has a workers’ compensation rating bureau that sets the proper standards for insurance premiums or self-insured fund.

[4] NCCI is the National Council of Compensation Insurance which developed the uniform Information page for workers’ compensation coverage in all 50 states. There are 14 NCCI monopolistic states where workers’ compensation insurance coverage can only be obtained through one statewide company or agency.

[5] Disclosure: The arbitrator in the Serrano and Toscano Corona cases is the author of this article.

[6] Select Staffing, as a general employer, had many special employer contracts. Select Staffing, as a general employer, had two insurance policies—one with ACE American Insurance Company, which listed the special employers with whom Select Staffing had Labor Code Section 3602(d)(1) contracts that did not include RSI Home Products listed as a special employer, and the other with Kemper Insurance Company, which did have RSI Home Products listed as a covered special employer.

Workers’ Compensation Laws: 50-State Survey

Reprinted with permission.

Professor Michael C. Duff of Saint Louis University School of Law is in the process of developing a very interesting and useful overview of workers’ compensation laws by state. His tool identifies the state law and administrative agency in each state, while summarizing the applicable reporting deadline and waiting period. In addition, each entry describes the disability benefits available in that state. This is a work in progress. Professor Duff says, “I am quite enthusiastic about the long-term value of developing this type of open source comparative information. We will get the best feedback possible with broad dissemination.” He asks that if you discover an error relative to your state, you report the error and the correct information to him via email: michael.duff@slu.edu.

Here is the link: https://sites.google.com/slu.edu/benefits-for-injured-workers.

A workplace accident or occupational disease can take a heavy toll on an employee. Medical bills and lost wages from time missed at work can mount quickly. Workers’ compensation programs aim to provide injured employees with the financial assistance that they need, while limiting the liability of employers. The concept behind workers’ compensation is a tradeoff between the employee and the employer. The employee cannot sue their employer (or a coworker) for compensation for their injuries, but they can recover benefits without proving that the employer was at fault. They need only prove that the accident occurred on the job.

In addition to covering medical treatment and potentially vocational rehabilitation, workers’ compensation offers disability benefits to eligible employees. These provide a partial replacement for lost income or earning capacity. Disability benefits are often defined by the extent and duration of the disability. The four standard types are permanent total, temporary total, permanent partial, and temporary partial disability benefits. However, some states define benefits differently. The formula for calculating each type of benefits also varies by state.

After an injury on the job, a worker needs to report the injury to their employer as part of the process of starting a claim. State laws may set a specific deadline for this notice. An employee thus must act promptly if they believe that they have suffered an injury on the job. In general, the deadline for reporting the injury is shorter than the deadline for filing a claim.

Each state imposes a “waiting period” before a worker can receive some or all types of disability benefits. If a disability lasts for a specified period, though, they usually can receive benefits for the waiting period retroactively.

This overview of workers’ compensation laws identifies the state law and administrative agency in each state, while summarizing the applicable reporting deadline and waiting period. In addition, each entry describes the disability benefits available in that state. Workers’ compensation laws can be extremely technical, and not every nuance is captured here. An employee should consider consulting a workers’ compensation lawyer if they have suffered a serious injury and expect to miss significant time from work.

Click on a state below to find out more about workers’ compensation benefits there.

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- Washington D.C.

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming

Alabama

- State law: Alabama Code Section 25-5-1 et seq.

- Administrative agency: Alabama Department of Labor, Workers’ Compensation Division

- Reporting deadline: 5 days

- Waiting period: Generally 3 days (retroactive if disability exists for 21 days)

For an injury causing a temporary total disability, Alabama workers’ compensation benefits are two-thirds of the average weekly earnings received at the time of the injury, subject to a statutory maximum and minimum. For a temporary partial disability, benefits are two-thirds of the difference between the average weekly earnings of the worker at the time of the injury and the average weekly earnings that they are able to earn in their partially disabled condition. These benefits last no more than 300 weeks.

Benefits for a permanent partial disability are based on the extent of the disability. For certain specified injuries, the compensation is two-thirds of average weekly earnings during the number of weeks in a statutory schedule. For other injuries, benefits are two-thirds of the difference between average weekly earnings at the time of the injury and the average weekly earnings that the worker is able to earn in their partially disabled condition. For a permanent total disability, the employee will receive two-thirds of the average weekly earnings received at the time of the injury, subject to a statutory maximum and minimum.

Alaska

- State law: Alaska Code Section 23.30.001 et seq.

- Administrative agency: Alaska Department of Labor and Workforce Development, Division of Workers’ Compensation

- Reporting deadline: 30 days

- Waiting period: 3 days (retroactive if disability lasts more than 28 days)

For a permanent total disability, Alaska workers’ compensation law provides that 80 percent of the injured employee’s spendable weekly wages will be paid to the employee during the continuance of the total disability. For a temporary total disability, 80 percent of the injured employee’s spendable weekly wages will be paid to the employee during the continuance of the disability, but not for any period after the date of medical stability.

For a temporary partial disability, the compensation is 80 percent of the difference between the injured employee’s spendable weekly wages before the injury and the wage-earning capacity of the employee after the injury. These benefits may not be paid for more than five years and may not be paid after the date of medical stability. For a partial permanent impairment, the compensation is $177,000 multiplied by the employee’s percentage of permanent impairment of the whole person.

Arizona

- State law: Arizona Revised Statutes Section 23-901 et seq.

- Administrative agency: Industrial Commission of Arizona, Claims Division

- Reporting deadline: Employee must “forthwith” report injury

- Waiting period: 7 days (retroactive if disability continues for 1 week beyond 7 days)

For a temporary total disability, Arizona workers’ compensation law provides that an injured employee will receive two-thirds of their average monthly wage during the period of disability. For a permanent total disability, compensation of two-thirds of the average monthly wage will be paid during the life of the injured person.

For a temporary partial disability, an injured employee will receive two-thirds of the difference between the wages earned before the injury and the wages that they are able to earn thereafter. A permanent partial disability caused by certain specified injuries will qualify a worker for compensation of 55 percent of their average monthly wage paid for a period provided by a statutory schedule, in addition to the compensation for temporary total disability. A permanent partial disability caused by other injuries will qualify an employee for compensation equal to 55 percent of the difference between the employee’s average monthly wages before the accident and the amount that represents their reduced monthly earning capacity resulting from the disability.

Arkansas

- State law: Arkansas Code Section 11-9-101 et seq.

- Administrative agency: Arkansas Workers’ Compensation Commission

- Reporting deadline: Generally unspecified; next regular business day when employee requires emergency medical treatment outside normal business hours

- Waiting period: 7 days; compensation for a disability beyond that period starts with the 9th day of disability (retroactive to 1st day of disability if disability extends for 2 weeks)

In the case of a total disability, Arkansas workers’ compensation law provides that an injured employee will receive two-thirds of their average weekly wage during the continuance of the disability. In the case of a temporary partial disability, an employee will receive two-thirds of the difference between their average weekly wage before the accident and their wage-earning capacity after the accident.

If an employee sustains a permanent partial disability based on a scheduled injury, they will receive weekly benefits in the amount of the permanent partial disability rate attributable to the injury for the period of time set out in the statutory schedule. These benefits are awarded in addition to compensation for temporary total and temporary partial benefits. If an employee sustains a permanent partial disability based on another injury, the disability will be apportioned to the body as a whole. This will have a value of 450 weeks. The employee will receive compensation for the proportionate loss of use of the body as a whole resulting from the injury.

California

- State law: California Labor Code Section 3200 et seq.

- Administrative agency: California Department of Industrial Relations, Division of Workers’ Compensation

- Reporting deadline: 30 days

- Waiting period: 3 days for temporary disability (retroactive if temporary disability continues for more than 14 days)

For a temporary total disability, California workers’ compensation law provides that the disability payment is two-thirds of the worker’s average weekly earnings during the period of the disability, while considering the ability of the injured employee to compete in an open labor market. For a temporary partial disability, the disability payment is two-thirds of the weekly loss in wages during the period of the disability. (The weekly loss in wages is the difference between the average weekly earnings of the injured employee and the weekly amount that they probably will be able to earn during the disability.) This payment will be reduced by the sum of unemployment compensation benefits and extended duration benefits received by the employee during that period.

California provides a statutory schedule for permanent partial disabilities. Also, if a permanent disability is at least 70 percent but less than 100 percent, 1.5 percent of the average weekly earnings for each 1 percent of disability in excess of 60 percent will be paid for the rest of the employee’s life. If the permanent disability is total, an injured employee will receive two-thirds of their average weekly earnings for the rest of their life.

Colorado

- State law: Colorado Code Section 8-40-101 et seq.

- Administrative agency: Colorado Department of Labor and Employment, Division of Workers’ Compensation

- Reporting deadline: 4 days (30 days after first distinct manifestation of occupational disease)

- Waiting period: 3 days for temporary total disability (retroactive if period of disability lasts longer than 2 weeks)

For a temporary total disability lasting more than three regular working days, Colorado workers’ compensation law provides that an employee will receive two-thirds of their average weekly wages, up to 91 percent of the state average weekly wage per week. For a temporary partial disability, an employee will receive two-thirds of the difference between their average weekly wage at the time of the injury and their average weekly wage during the continuance of the disability, again up to 91 percent of the state average weekly wage. For a permanent total disability, an employee will receive two-thirds of their average weekly wages for the rest of their life, but not more than the weekly maximum benefits for temporary total disability.

Permanent partial disability benefits are also known as medical impairment benefits in Colorado. These are based on permanent loss of function or impairment to a body part. The amount of permanent partial disability benefits that a claimant may receive is calculated by using the percentage of loss determined by the doctor and a statutory formula.

Connecticut

- State law: Connecticut General Statutes Section 31-275 et seq.

- Administrative agency: Connecticut Workers’ Compensation Commission

- Reporting deadline: Immediate, but failure to do so does not affect benefits unless employer can show prejudice

- Waiting period: 3 days (retroactive if incapacity continues for 7 days)

If an injury for which compensation is provided under the Connecticut Workers’ Compensation Act results in a total incapacity to work, the injured employee will receive weekly compensation equal to 75 percent of their average weekly earnings as of the date of the injury, subject to a maximum weekly benefit rate.

If an injury results in partial incapacity, the injured employee will receive weekly compensation equal to 75 percent of the difference between the wages currently earned by an employee in a position comparable to the position held by the injured employee before their injury and the amount that the employee is able to earn after the injury. This compensation will not be more than 100 percent of the average weekly earnings of production and related workers in manufacturing in the state and will last no longer than 520 weeks. A specific schedule applies to certain injuries identified by statute.

Delaware

- State law: 19 Delaware Code Section 2301 et seq.

- Administrative agency: Delaware Department of Labor, Division of Industrial Affairs, Office of Workers’ Compensation

- Reporting deadline: 90 days (6 months for occupational diseases)

- Waiting period: Generally 3 days (retroactive if incapacity extends to 7 days)

For injuries resulting in a total disability, the compensation to be paid under Delaware workers’ compensation law is two-thirds of the wages of the injured employee. However, this compensation must not be more than two-thirds of the average weekly wage per week as announced by the Secretary of the Department of Labor, or less than 22 2/9 percent of the average weekly wage per week.

For injuries resulting in a partial disability, with some exceptions, the compensation to be paid is two-thirds of the difference between the wages received by the injured employee before the injury and the earning power of the employee thereafter. However, this compensation cannot be more than two-thirds of the average weekly wage per week as announced by the Secretary of Labor. This compensation is limited to 300 weeks. A specific provision applies to compensation for certain permanent injuries.

Florida

- State law: Florida Statutes Section 440.001 et seq.

- Administrative agency: Florida Department of Financial Services, Division of Workers’ Compensation

- Reporting deadline: 30 days

- Waiting period: 7 days (retroactive if more than 21 days of disability)

For a permanent total disability, Florida workers’ compensation law provides that an injured employee is entitled to two-thirds of their average weekly wages. For a temporary total disability, the employee also is entitled to two-thirds of their average weekly wages, but this generally will not exceed 104 weeks. Once the employee reaches the 104-week limit or reaches the date of maximum medical improvement, whichever is earlier, temporary disability benefits will cease, and their permanent impairment will be determined.

Permanent impairment income benefits (similar to permanent partial disability benefits) are based on an impairment rating that uses an impairment schedule. These benefits are paid biweekly at the rate of 75 percent of the employee’s average weekly temporary total disability benefit, subject to some limitations. For a temporary partial disability, meanwhile, compensation is equal to 80 percent of the difference between 80 percent of the employee’s average weekly wage and the salary, wages, and other remuneration that the employee is able to earn after the injury, as compared weekly.

Georgia

- State law: Georgia Code Section 34-9-1 et seq.

- Administrative agency: Georgia State Board of Workers’ Compensation

- Reporting deadline: Immediately or as soon as practicable, but at least within 30 days

- Waiting period: 7 days (retroactive if employee is incapacitated for 21 days)

For a temporary total disability, Georgia workers’ compensation law provides that an employee will receive a weekly benefit equal to two-thirds of their average weekly wage, subject to a minimum and maximum. This benefit is generally payable for no more than 400 weeks after the injury. However, when an injury is catastrophic, the weekly benefit is payable until the employee’s condition improves.

For a temporary partial disability, an employee will receive a weekly benefit equal to two-thirds of the difference between their average weekly wage before the injury and the average weekly wage that they are able to earn thereafter, but not more than $450 per week. These benefits will be paid for no more than 350 weeks after the injury. For a permanent partial disability, which is a disability resulting from the loss or loss of use of body members or the partial loss of use of the employee’s body, the employer will pay weekly income benefits to the employee according to a statutory schedule.

Hawaii

- State law: Hawaii Revised Statutes Section 386-1 et seq.

- Administrative agency: Hawaii Department of Labor and Industrial Relations, Disability Compensation Division

- Reporting deadline: As soon as practicable

- Waiting period: 3 days for temporary total disability

For a permanent total disability, Hawaii workers’ compensation law provides that an employee will receive a weekly benefit equal to two-thirds of their average weekly wages, but not more than the state average weekly wage nor less than a certain minimum. For a temporary total disability, the employee will receive a weekly benefit at the rate of two-thirds of their average weekly wages, subject to the same limitations.

For a permanent partial disability, an employee will receive compensation in an amount determined by multiplying the maximum weekly benefit rate prescribed by statute by the number of weeks specified for the disability in a statutory schedule. (Benefits are also available for non-scheduled injuries, for which more complex rules apply.) For a temporary partial disability, an employee will receive weekly benefits equal to two-thirds of the difference between their average weekly wages before the injury and their weekly earnings thereafter, subject to the schedule for the maximum and minimum weekly benefit rates.

Idaho

- State law: Idaho Code Section 72-101 et seq.

- Administrative agency: Idaho Industrial Commission

- Reporting deadline: As soon as practicable, but no later than 60 days

- Waiting period: 5 days (retroactive if disability exceeds 2 weeks)

According to Idaho workers’ compensation law, an injured worker will receive total disability benefits in an amount equal to 67 percent of their average weekly wage for a period no greater than 52 weeks. After that time, total disability benefits are paid in an amount equal to 67 percent of the currently applicable average weekly state wage. These amounts are subject to a minimum and maximum. Certain injuries are deemed total and permanent unless the employer can prove otherwise by clear and convincing evidence.

For partial disability during the period of recovery, an injured worker will receive an amount equal to 67 percent of their decrease in wage-earning capacity, but this must not exceed the income benefits payable for total disability. Idaho also offers scheduled income benefits for the loss or loss of use of a bodily member. These are paid in addition to income benefits payable during the period of recovery when a permanent disability is not total. A separate rule applies to non-scheduled permanent disabilities that are not total. The wage factor in the formula for calculating benefits for a permanent but not total disability is 55 percent of the average weekly state wage.

Illinois

- State law: 820 Illinois Compiled Statutes Section 305/1 et seq.

- Administrative agency: Illinois Workers’ Compensation Commission

- Reporting deadline: As soon as practicable, but no later than 45 days

- Waiting period: 3 days of temporary total incapacity (retroactive if temporary total incapacity continues for 14 days)

For a temporary total disability, Illinois workers’ compensation law provides that an injured employee will receive two-thirds of their average weekly wage, subject to a minimum and maximum. For a permanent total disability, an injured worker will receive two-thirds of their average weekly wage for life, subject to a minimum and maximum. For a temporary partial disability, an injured worker will receive two-thirds of the difference between the average amount that they would be able to earn in their pre-injury job and the gross amount that they earn in their light-duty job.